Firearms Technical Trivia, May 2000:

|

|

|

The United States Army has often been accused of being one of the most reactionary, traditional, and hidebound organizations in the world when it comes to small arms developments. Proponents of this school of thought point toward the adoption of the M14 rifle over the FAL or the nascent AR-15, or the way that the Army Ordnance establishment championed the 7.62mm NATO cartridge despite the availability of many well designed intermediate cartridges, as proof positive that the United States Army simply did not want to "come into the 20th Century" with respect to small arms development.

While this may have been true of some segments of the Army Ordnance establishment, other parts of the organization were operating on the cutting edge of technology in an effort to address the actual combat needs of the service. In this article, we will discuss the development of the small arms flechette projectile that resulted from the Army's thorough analysis of the behavior of the man-rifle system in World Wars One and Two and the Korean War.

ORO STIRS UP THE POT

In September 1948, the US Army created the Operations Research Office (ORO), whose initial mandate was to supply the Army with scientific data and advice about the conduct of nuclear war. The outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 caused the Army to extend ORO's mandate to a host of non-nuclear problems, which included improved artillery, anti-aircraft operations, and matters germane to infantry warfare. As a result, an Infantry division within ORO was created, and a Mr. Norman Hitchman placed in charge. One of the Infantry Division's first tasks was to study methods for improving body armor (Project ALCLAD). As part of Project ALCLAD, a thorough study of battlefield projectile hazards (bullets and shell fragments) was undertaken. As a result of these efforts, ORO produced a report that challenged the Army's deeply ingrained traditions of firepower, marksmanship, and combat riflery.

Prior to the release of the ORO report, however, the Army's Ballistic Research Laboratories (BRL), located at the Aberdeen Proving Grounds, Aberdeen, Maryland, released a report dated March, 1952 analyzing the effectiveness of the infantry rifle. (The report had been commissioned as a result of the finding that approximately 50,000 rounds were expended per enemy casualty in World War Two.) The report was a blow to the Army's ".30 Caliber Mafia," as it espoused the idea that bullets of around .22 caliber or smaller could produce lethality results equal to or better than the .30 caliber projectiles if their velocity could be kept high enough:

The theoretical consideration of a family of rifles indicates that the smaller caliber rifles than .30 have a greater single shot kill probability than the cal. .30 M1. This is obtained by increasing the muzzle velocity and thereby obtaining a flatter trajectory, so that the adverse effects of range estimation errors is reduced. When the combined weight of gun and ammunition is held constant at fifteen pounds, the overall expected number of kills for the cal. .21 rifle is approximately 2.5 times that of the present standard cal. .30 rifle. If the number of rounds is fixed at 96, the total load carried by the soldier with a cal. .21 rifle and ammunition with 0.6 the charge in the M2 cartridge will be 3.6 lbs less than that carried by a soldier with a cal. .30 M1 rifle. This is a 25% reduction in load.The BRL study was followed in June 1952 by the ORO study, entitled Operational Requirements for an Infantry Hand Weapon. The report discussed just how well the current generation of infantry rifles had performed their assigned tasks:Furthermore, if it were necessary for a soldier with the M1 to carry the rounds required for the same expected number of kills at 500 yards as a a soldier with fifteen lbs of cal. .21 6/10 charge rifle and ammunition, it would be necessary for him to carry ten lbs more ammunition, or a total load of 25 lbs.

. . . rifle fire and its effects were deficient in some important military respects. . . in combat, hits from bullets are incurred by the body at random: . . .the same as for fragment missiles which are not "aimed" . . .Exposure was the chief factor. . .aimed or directed fire does not influence the manner in which hits are sustained. . . Despite evidence of prodigious rifle fire ammunition expenditure per hit, . . .the comparison of hits from bullets with those of fragments shows that the rifle bullet is not actually better directed towards vulnerable parts of the body.Moreover, ORO report demonstrated that from all the British and American data available, 80% of effective rifle and light machinegun fire had been reported at ranges under 200 yards, with fully 90% under 300 yards. The problem, said ORO, was not with the rifle, but with the man:

Errors in aiming have been found to be the greatest single factor contributing to the lack of effectiveness of the man-rifle system. . .in combat, men who are graded. . . as expert riflemen do not perform satisfactorily at common battle ranges.The ORO report's suggested solution to this problem was to compensate intentionally for the soldier's aiming errors by developing a new type of automatic weapon capable of projecting missiles either in burst or salvo.

Image Credit: Stevens, R. Blake and Edward C. Ezell, The SPIW: The Deadliest Weapon That Never Was, Collector Grade Publications, Toronto, 1985, Page 15 |

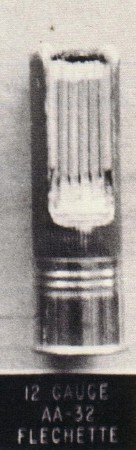

With

the publication of these reports, the multi-agency Project SALVO, which

sought new answers to increasing the rifle and rifleman's combat efficiency,

was initiated in November of 1952. One of the products tested during

the SALVO studies, was a 12 gauge shotshell manufactured by Aircraft Armaments,

Inc. (AAI) of Cockeysville, Maryland, which was loaded with 32 nested steel

arrows, or flechettes, each weighing about eight grains. While the

studies noted that the shotshell had deficient control with respect to

dispersion, it was noted that the .087 caliber flechettes would typically

perforate one side of an M1 steel helmet and liner at 300 yards, and sometimes

do so at ranges of up to 500 yards.

As a result of the SALVO studies, ORO analysts became enthusiastic about the possibilities of marrying the BRL concept of high velocity and resultant flat trajectory with the almost negligible recoil impulse that would be generated by the small caliber, lightweight, single flechette. ORO recommended exploring this |

But first, the new round had to be developed. . .

AAI AND THE SERIAL FLECHETTE

AAI had a degree of experience with flechettes, owing to the shotshell project. For several years after the time of the shotshell project, AAI continued to experiment with the single flechette idea without any outside funding, gambling that the flechette's advantages of minimal recoil, high penetrating power and light weight would not go unnoticed.

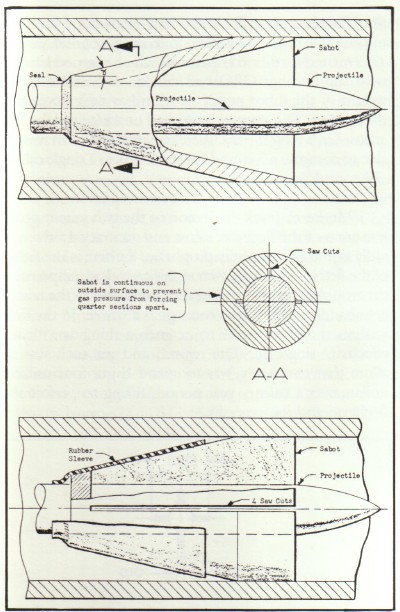

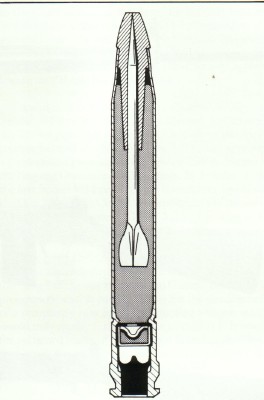

Unlike

rifle bullets, which are stabilized by the spinning motion imparted to

them by the rifling's twist as they pass down the barrel, the flechette

is stabilized in flight by its integral fins, which are of a greater diameter

than the body of the flechette itself. Rifling was therefore found

to be unnecessary, and the flechette is designed to be fired from a smoothbore

barrel, of a diameter slightly larger than that of the fins. Two

considerations immediately make themselves evident: guiding the body

of the flechette down the barrel, and providing an adequate gas seal around

the flechette. The solution to this problem was found in the form

of the sabot, a segmented, bore sized plug which would either sit behind

the flechette and push it, or grip the body of the flechette and pull it

down the bore.

| Initially, AAI designs used a pusher type of sabot, but this was soon discarded as it would make the cartridge too long since the propellant would have to be packed behind the long projectile and the sabot. AAI took inspiration from German World War Two cannon ammunition which had used an arrow-like projectile with a sabot located at the center of the projectile. This design transmitted the gas propelling force from the sabot to the projectile by means of threads. The metal sabot itself was split into four pieces and retained by the barrel, separating at the muzzle. The use of threads on the rifle caliber flechette was discounted as it increased drag and limited the pulling force. The AAI flechette used a new concept, where the projectile was pulled by a sabot which surrounded the forward part of the projectile and used a lightweight metal or plastic sabot. The |

The "Chuck Effect" Image Credit: Stevens, R. Blake and Edward C. Ezell, The SPIW: The Deadliest Weapon That Never Was, Collector Grade Publications, Toronto, 1985, Page 23 |

Flechette Stripper Device Image Credit: Stevens, R. Blake and Edward C. Ezell, The SPIW: The Deadliest Weapon That Never Was, Collector Grade Publications, Toronto, 1985, Page 19 |

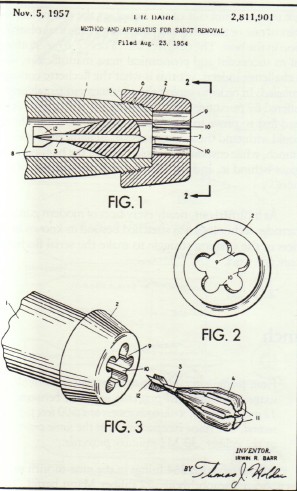

Experiments were conducted, testing many designs and materials for the puller sabot, and the chuck concept was vindicated. During the early trials in March 1954, several flechette rounds were fired from a .22 rifle using sabots machined from fiberglass rods. Oddly, some of the sabots would function perfectly while in the bore (i.e. pulling the projectile without blowing off), but would not break apart and fall away from the flechette at the muzzle. The solution was to add a short extension to the muzzle. The extension resembled a threading die. There were internal projections similar to large angle rifling set at a five degree twist. This device, known as the "stripper," scored and imparted a violent spin to the sabot as it left the muzzle. The resultant shock and centrifugal force ensured that the sabot's segments would fly apart and not cling to the flechette during flight. AAI applied for patents on |

The key to the single flechette's effectiveness was velocity. The original BRL report suggested that for a 50 grain .22 caliber projectile to attain the wounding characteristics of the service .30 caliber round, it would have to have a muzzle velocity of some 3,500 feet per second. For a ten grain flechette, the velocity would have to be significantly higher. Additionally, the action of the sabot was crucial. Just as it must fall away after the projectile exited the muzzle, it must not separate until after the exited the muzzle, lest an extremely dangerous obstruction remain in the bore.

The Army development contract for the flechette was let in 1956. During the development phase, the idea of the puller sabot gripping by pressure alone proved to be an elusive quarry. The puller sabots were made of variously shaped pieces of aluminum, brass, or steel. Despite the various materials tried, it was still found that the sabot's grip on the flechette had to be assured by mating it with either a threaded section of the flechette of with a reduced diameter section of the flechette body. This proved unsatisfactory - as the velocity neared 4,000 feet per second, the tensile stresses on the flechette approached 200,000 pounds per square inch, and any thrust shoulder or thread undercut would fail, resulting in the flechette being literally pulled in half.

Continued experiments determined more of the flechette's design limitations. .088 inches was the minimum diameter which would withstand the tensile stresses of the high velocity launch. Since this was the diameter of the flechette body itself, the decision was made to use a sabot which would transmit the pulling force to the smooth body of the flechette through friction alone. It was also found that an ogival form to the flechette's nose gave better terminal velocities than a semi-blunt one. Too much projectile weight would result in the sabot being pulled off in the bore, and the sabot segments had to be very meticulously fashioned to provide an effective gas seal.

Problems were found with the one-piece design of the aluminum sabot, which was carefully slit for nearly its entire length into quarters and then sheathed from the rear with a thin rubber sleeve. While this performed satisfactorily in terms of keeping the sabot and flechette together inside the barrel, and acting as a gas seal, it failed to separate from the projectile upon exiting the barrel. Experiments with slit length and sabot thickness failed to produce satisfactory results. Finally, the development team took a new look at one of the program's basic tenets. The original intent had been to launch a fin stabilized projectile at about 4,000 feet per second from the shortest possible cartridge case. The problem with the shortest possible case meant that the use of small-grained, rapid burning powder, which required comparatively little case volume was necessary. The sabot failures were finally traced to to the nearly instantaneous high breech pressures generated by this type of powder. Further experiments in 1956 led to the use of slower burning Olin ball powder (type WC660H) in a somewhat longer case. This produced a slower rise in breech pressure, allowing the use of the more reliable threaded sabots and projectiles. These now launched and separated properly, giving satisfactory accuracy results at 100 yards.

After all the experiments and tests, a flechette weighing 10 grains was settled upon as the basis for all subsequent experimentation.

The final

version of AAI's ".22 Caliber, Single Flechette Ammunition" responded to

two further Army R&D contracts in 1959. One of the most interesting

features of the, slim, belted AAI cartridge was the unique multipiece piston

primer assembly. There was ample historical precedent for the use

of a primer actuated design. Indeed, John Garand had proposed a rifle

design in the mid-1920's for Springfield Armory that had been primer actuated.

However, the AAI piston primer differed from the Garand design, which had

been built around standard military cartridges with standard primers.

Each example of the AAI piston primer actually contained the front half

of its own firing pin!

| During the assembly process, the piston primer was inserted down through the neck of the case and held securely against forward movement by a crimp (which appeared as four distinctive dimples in the outside circumference of the case). It was positioned slightly forward inside the primer pocket, and was designed to be fired by a blow from the weapon's flat faced firing pin. This blow would collapse the whole piston forward, the frontal point of the piston would detonate the priming compound and ignite the powder charge. The resultant pressure inside the case |

Flechette Piston Primer Image Credit: Stevens, R. Blake and Edward C. Ezell, The SPIW: The Deadliest Weapon That Never Was, Collector Grade Publications, Toronto, 1985, Page 27 |

The puller sabot was eventually made from four pieces of a lightweight magnesium alloy which were first glued together and then turned to shape as a single piece in order to assure positive gas sealing.

In May 1960 the AAI proprietary designation was given the official nomenclature, "Cartridge, 5.6mm, XM110."

The story of the flechette cartridge is one of engineering triumph at the edge of what was technologically possible, and a feather in the cap of the much maligned American "military-industrial complex." While now little more than a footnote in the history of American martial firearms development, the story XM110 and the weapon designed to use it, the Special Purpose Individual Weapon (SPIW) is one whose repercussions are still being felt today, and one that merits study by all who have an interest in the history, development, technology, and procurement of small arms by the United States military.

Note: Data for this month's trivia page was gathered from:

Stevens, R. Blake, and Edward C. Ezell, The SPIW: The Deadliest Weapon That Never Was, Collector Grade Publications (Toronto, 1985) ISBN 0-88935-018-3

The

SPIW: The Deadliest Weapon That Never Was is available from IDSA

Books. Click on the image to order.